Verónica Ramírez

Verónica Ramírez

Back to square one after surviving hell in Libya

Hundreds of migrants return to The Gambia after crossing the Sahara, getting scammed by human traffickers, abused and sold into slavery at the last border on their way to Europe.

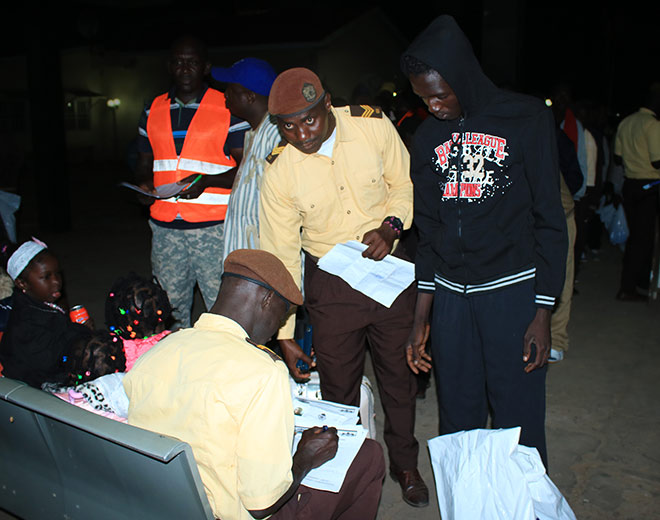

The migrants return from hell on Earth and when they get off the plane at Banjul airport, their government promises them a papier-mâché paradise. It is eleven at night and 230 Gambian migrants have just arrived on a charter flight from Libya. Henry Gomez, the Gambian Minister of Youth and Sports, tells them, “You didn’t achieve it abroad, but you can be millionaires in The Gambia.” The flight is one of a growing number of repatriations carried out by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the European Union, and several African countries over the last few weeks in the wake of human rights violations in Libya.

In Gomez’s pep talk, which interrupts passport and paperwork checks, he promises that the doors of government are open to the migrants and he calls for patience. “Slowly, slowly, you can catch a monkey,” he says, quoting a folk saying in Wolof, a local language.

The Minister of Youth and Sports, Henry Gomez, rallies migrants fresh off the airplane. | Verónica Ramírez

Some prefer to look away but some applaud the speech. Then Gomez says, “When you left, the country was as tranquil and silent as the grave. The women couldn’t have husbands… now that you are back the women will be happy.” People cheer that. Most of the returnees are young men. Of 230 passengers on the flight, just six are children and three are women.

One of the women is carrying three children and a baby born during her journey. She is one of the first to go through passport control. Although The Gambia is warm the whole year, it is nighttime in December and the cold is beginning to press in a little. As she completes the paperwork, the two smallest children fall sleep at her side, wrapped in jackets. Then the woman’s sister arrives at the airport to greet them.

Omar, 13, returns to The Gambia after a long journey with his father. | Verónica Ramírez

Omar is 13 years old and traveled with his father from The Gambia to Senegal, then to Mali and Burkina Faso, and finally onward to Niger and Libya. The journey took them almost a year, about the same as for the other migrants. At one point, they had to ask Omar’s mother, who stayed behind in The Gambia, to send more money. This is a recurring story: the money the migrants set aside for the journey is never enough. The families had to send more, in some cases taking on debts or going hungry to pay endless bribes to traffickers or to get the migrants out of jail. Almost in passing, Omar mentions that they were badly treated on the journey. What he really wants to talk about is how eager he is to go back to school.

Many of the migrants are young men dressed in IOM-issued gray and white cotton tracksuits. Some joke about the journey and celebrate being home again. Others stare at the ground. All are tired. They have tried two, three, four, five times to reach Europe from Libya. They have paid traffickers to cross, they have been detained, spent time in jail, suffered abuse, paid to get out of jail, paid more to cross again, worked for no pay, were sold into slavery, been detained again, got out, paid again and tried again. They lived out these stories on a loop.

Abass recovers after the trip in a Banjul airport lounge. | Muna Manneh-Fye

Abass took nine months to reach Tripoli. The scam hit him after crossing the continent. “They take your money and don’t give you anything in return,” he says. As the migrants wait in the airport lounge for lodgings for the night, they snack on cookies and soft drinks in their welcome packs. Ibrahim complains, “They ask you for money to introduce you to someone with a boat. You pay twice, three times, and you never cross.” If you do manage to cross, your odds of reaching Italy are not too rosy. As of the 29th of November 2017, 2,631 people had died this year crossing the central Mediterranean route to Europe, the OIM reports.

Ibrahim explains how traffickers put 150 people in a boat built for 50, in bad weather. Many died there. “They call it an accident,” he says with half a smile. “We didn’t pay Nigerians or Senegalese. We paid Gambians because we trusted them and they put you in that boat where you’re going to die,” he says.

Accusations of murder, abuse, and slavery in Libya

Whether at sea or on land, migrants were likely to be detained at some point. Ibrahim was arrested on the beach just before trying to cross, he says: “They attacked the camp. They said they wanted to cleanse the country, that they were going to cleanse the country of blacks.” In prison, officials barely gave them anything to eat. “They gave you a piece of bread one day and none the next,” he says. But the worst part, Ibrahim says, was the treatment: insults, abuse. “No mercy,” he says forcefully. Five months ago, someone shot a Gambian in front of him. “He didn’t do anything. They were arguing and they killed him,” he says.

Ibrahim: “No mercy in Libya”. | Muna Manneh-Fye

To get out of jail that time, Ibrahim had to pay 25,000 dalasis (about 450 euro), which his brother sent him from The Gambia. Then he had to look for work to pay for another attempted crossing. But Ibrahim always had trouble when it came time to collect his pay. Like the other migrants in the airport, he claims he worked for months without pay and that he could not do anything about it because the people scamming him were on home turf. It is a “lawless” country, he explains. “You pay a trafficker you trust and he sells you to the Libyans. They treat you like a slave,” he adds.

One of his travel companions approaches and explains that he also worked for months. When he tried to collect his pay, all he got was a “no” and a Kalashnikov pointed his way.

Later, he spent half a year in the hospital for a bullet wound because someone shot him in the back during another arrest. He touches his scar and recalls, “Thank God I’m not dead, but most of my Gambian friends died there. I saw it. Many of them.”

That was one of his attempts to cross, but there were three more. Whether he was detained on the boat, on the beach, or in the city, each time meant going back to jail, paying again to get out, and working like a slave.

Ousman is 21 years old. His story is very similar to those of his companions. He remembers, along with other degrading treatment, how a lot of Libyans covered their noses when he passed by.

Paperwork upon entering the country. | Muna Manneh-Fye

They have all devoted a year or more of their lives to crossing to Europe. Things have changed since they began their journeys. When they left, dictator Yahya Jammeh had been in power for more than 20 years and racked up multiple accusations of human rights violations and sexual and press repression. Until recently, there was only one, state-owned, television channel. Now there are two.

Perhaps more important, in January 2017, Adama Barrow became the new president in democratic elections. While the migrants wait to complete their paperwork, the minister continues his harangue: “You brought change to this country, you threw out the previous government. Gambia is your Gambia.” It is never a bad time to campaign.

Now they are back to square one after a long hard journey without a happy ending. Would they try again? For Ibrahim, there is no way. Instead, he wants to go back to being a driver, he says: “I’ve seen too many things there. People who die in prison, deadly beatings.” He swears he will not cross again and would not wish it on anyone else.

Verónica Ramírez (images), Modou Lamin Ceesay (translation from wólof and mandinqa), Muna Manneh-Fye (images) and Lucas Laursen (English editing) also contributed to this article.