Spanish prisons use a 30-year-old algorithm to decide on temporary releases

More than 200 court rulings in 2024 cite an algorithm that classifies foreign prisoners without ties as high risk, even if they lack other risk factors.

In 1993, when the Ministry of Justice commissioned psychologist Miguel Clemente to develop a predictive tool for criminal behaviour, it was unusual to hear the word “algorithm.” Earlier that year, two beekeepers found in a grave the bodies of Toñi, Miriam and Desiré, the victims of the Alcàsser crimes. The event shocked the country. One of the perpetrators had escaped the previous year while on temporary release from prison.

The Alcàsser crime led to the creation of the Risk Factor Table (TVR in Spanish), a ten-factor formula which, 32 years later, prison professionals still use to decide whether to grant temporary release. In 2024 alone, more than 200 provincial court decisions cite it as a compelling reason for granting or denying temporary release, several of them against the prison’s own recommendation.

“The context was very pressing,” recalls Clemente, now a professor at the University of A Coruña and an expert in legal psychology. As a result of the Alcàsser crime, he says, people began to question the security of temporary release, one of the measures in the 1979 Penitentiary Law intended to prepare prisoners for life after incarceration.

The creators of the TVR sought to provide a certain degree of security, with scientific and objective parameters, when deciding on the granting of temporary release. At that time, says José Ángel Brandariz, also a professor at the University of A Coruña and an expert in criminal law, there were practically no precedents for similar tools in any prison system in the world: “In those years nobody was doing that… only the Canadians, to whom nobody paid attention.” The only precedent in Spain, Clemente says, was a small questionnaire derived from a 1988 statistical study by Santos Rejas, then a psychologist at the Badajoz penitentiary.

To develop the TVR, Directorate General of Penitentiary Institutions (IIPP in Spanish) staff worked with researchers from the Complutense University, led by Clemente. The field work to design the algorithm, described in the 1993 report Validación y depuración de la Tabla de Variables de Riesgo en el disfrute de Permisos Penitenciarios de Salida, was based on 18 variables suggested by IIPP, to which Clemente’s team added three: gender, age and sentence length. The study analysed a sample of nearly 1,500 inmates, a third of whom had not been on temporary release, a third of whom had been on release and returned to prison as required, and the remaining third whom absconded.

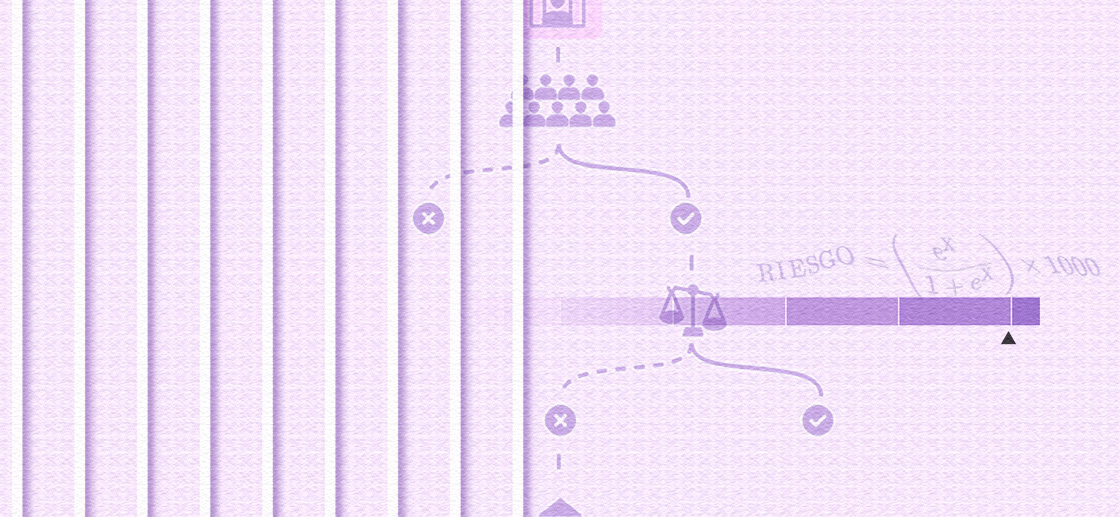

The study identified a total of ten risk factors: foreignness, drug dependency, criminal professionalism, recidivism, previous offences, whether they are in a closed regime, whether they had done previous temporary releases, domestic violence or other problems, distance of the release location from the prison, and internal pressures such as threats or aggression with other inmates. The authors assigned scores from 0 to 3 for each factor and gave each factor a specific weight in their overall equation. The result is a percentage value that starts from very low risk, defined as 5%; normal, between 20 and 35%; and high risk: 40% and up, much more restrictive assessments than the authors first proposed. According to Clemente, the risk range should be centred on 50 out of 100. “What the administration is doing is setting it at 35%, to prevent more inmates from going out on the street to avoid problems, even if it is at the cost of their rehabilitation,” Clemente says. “I commented on it, but they told us that it was not up to us,” he says.

IIPP added one more resource: the Table of Concurrence of Peculiar Circumstances (CCP in Spanish), a list of questions, without any mathematical formula, which included whether the score on the TVR is equal to or higher than 65%, whether the prisoner had been convicted of certain crimes, such as gender violence or sexual violence, the social impact of the crime committed, the time remaining for the inmate to serve three quarters of their sentence, whether the inmate suffers from a psychopathological disorder and whether the inmate is subject to deportation.

“If you’re a foreigner, you’re screwed”.

Of the nearly 1,500 prisoners who made up the sample in the TVR study, almost 1,200 were Spanish and, of the foreigners, only 83 were from outside the European Union with no links to Spain. Despite this, according to the formula and values in the study, the TVR assigns a maximum risk score to non-EU prisoners with no ties to Spain, even if they have the lowest scores for the other factors. Several academic articles by IIPP professionals, such as the lawyers Puerto Solar Calvo and Lucía Pérez Arnaldo, have criticised this. “Penitentiary Institutions were of the opinion, and they said that based on previous cases and multiple interviews, that nationality was a key factor when it came to a smooth fulfilment of the temporary release,” Clemente says.

The TVR assigns its maximum risk to non-EU prisoners with no ties to Spain, even if they have the lowest score for the other factors.

Several lawyers also highlight other factors in the table that do not depend on the prisoner’s behaviour, such as the distance of temporary release from the prison, the lack of family support or the absence of previous temporary releases, a vicious cycle.

“If you are a foreigner without ties, you’re screwed; but, even if you have ties, if you add that you have not taken any temporary release before or because you would take it more than 400 km from the penitentiary because you live in Galicia and you are serving a sentence in Madrid, they don’t give you release either,” says Carlos García Castaño, lawyer coordinator since 1995 of the Prison Legal Aid Service (SOJP in Spanish) of the Bar Association of Madrid.

Margarita Aguilera, assistant coordinator of SOJP Madrid and a lawyer of the Association of Collaborators with Women Prisoners (ACOPE) also criticises the fact that this tool is applied to women prisoners despite that only 62 of the nearly 1,500 people analysed for the development of the TVR were women. “In addition to the fact that it is obsolete, based on a population that has nothing to do with the current one because many years have passed, women are not represented in that population, they are in a minimum percentage, and the reasons why they might breach a temporary release have nothing to do with those of men,” she says.

Of the nearly 1,500 prisoners in the sample used to design the algorithm, only 62 were women.

But how predictive is TVR? If you compare prisoner scores and whether or not they have actually absconded, the algorithm is right from 53.33% to 69.69% of the time, depending on the level of risk.

Clemente says that there should have been a plan for the constant evaluation and updating of the tool, but he is not aware of such a plan or any updating. “I have never been told about renewal or anything else, and to date I have not heard anything, which seems serious to me,” he says. IIPP confirmed to Civio that the only change made to the TVR was in the early 90s, to include gender violence and deportation orders in the CCP. “For the prison administration, the TVR is just another tool, but it is not a determining factor in the analysis process. What is really decisive is the holistic study carried out by the technical team of the penitentiary centre, a complex and multifactorial study,” an IIPP spokesperson wrote in a statement.

A “whitewash” for the treatment board and a compelling reason in court

Instruction 22/1996 describes the process of granting temporary release, the basic requirements of which are to have served a quarter of the sentence, to be serving second- or third-degree confinement and lack a history of misconduct. It explains that the treatment boards and their technical team, made up of psychologists, sociologists, medical educators and social workers, among others, are responsible for studying whether to grant or deny a temporary release, using, among other tools, the TVR and the CCP.

The temporary release process

María Yela has been a prison psychologist in various prisons since 1982 and, although she was not formally involved in the design of the TVR, she was very close to the process. In those years she organised workshops in Cáceres prison to prepare prisoners for their first temporary release. “We started to draw indicators and the Risk Factors Table has collected many of them,” she says. The TVR does not determine the decision of the treatment boards, she says: “There are inmates who get a good score, but the board does not see them as ready, and vice versa, others who do not get the score, but we believe that it is their time, that they need to get outside.”

“There are inmates who get a good score, but the board does not see them as ready, and vice versa, others who do not get the score, but we believe that it is their time, that they need to get outside,” María Yela says.

Ana Gordaliza, a social educator at the Valdemoro prison and member of the working group on mental health in prison of the Spanish Association of Neuropsychiatry, says that, rather than determining the treatment board’s decision, the TVR serves as an embellishment. “I think it is the tool we use on many occasions when we want to give a slightly scientific whitewash to a decision that has been taken beforehand.” As a social educator, she participates with a voice, but without a vote, in the decisions of the treatment board, including her assessments in the report on the granting of temporary releases. She explains that, for example, if the board considers a foreign inmate ready for release, they do not mention the TVR. “Maybe you give a more detailed report, emphasising what I think should be our job: ‘He has a host and he will spend his release with them, he has no drug problems’…”.

Although the tool is not decisive for the treatment boards, the instructions on temporary releases, including the latest one, from 2012, oblige treatment boards to give special reasons for their recommendations if they contradict the TVR, and to include it in the report to the prison supervisory court, which oversees temporary releases, and the provincial courts, which have final say over appeals.

“The judges are the ones who grant the temporary releases and, as far as I know, they pay quite a lot of attention to the TVR,” Clemente says. García Castaño says that prosecutors continually cite whether the TVR is high or low risk in the reports they provide to prison supervisory courts and provincial courts when deciding on temporary releases.

“Most of the temporary release I have obtained has been through appeals to the Provincial Court,” Borja says, until recently an inmate in Valdemoro prison and now serving third-degree confinement. In 2001 he was granted temporary release for the first time, having served eight years of a 34-year sentence. “I had applied for it at least five or six times before,” he recalls. He explains that the notification of the refusal of release by the treatment board included several reasons. “For example, long sentence, established criminal record, or that three quarters of the total sentence is far from being served,” he explains. This was accompanied by an acronym and a number. “In one row they put TVR and then a small number, but they don’t say what it is.”

With each refusal, Borja filed a complaint with the prison supervisory court. But until prisoners appeal to the Provincial Court, the only thing they know about the TVR is a number. “The board informs the inmate whether or not he or she is granted temporary release, and if not, the inmate can file a complaint, but without having seen the board’s report,” explains lawyer Daniel Amelang. “Once the complaint is dismissed, we file an appeal to the Provincial Court and the lawyers do get the report,” Amelang says.

In Borja’s case, despite the board’s report, with a negative TVR assessment, the Provincial Court of Madrid accepted his appeal, granting him temporary release as he had served the necessary time of sentence, had no misconduct and, moreover, participated in the centre’s activities.

At least 37 decisions in 2024 issued by provincial courts rely on the TVR to grant or deny temporary releases against the criteria of the treatment board.

The Judicial Documentation Centre has published, only in 2024, at least 250 rulings by 19 provincial courts citing the TVR, 102 of them from Madrid. The vast majority of the rulings, 206, are based on the result of the algorithm to decide on the prisoner’s temporary release from prison. 37 of them overrule the treatment board’s recommendation. Some 169 rulings refuse permission because the TVR result ranges from “high risk” to “maximum.” Other judgments overruling a treatment board’s recommendation for release even cite “normal” TVR scores, but rule it an “unacceptable” risk, lowering the threshold of acceptable risk even further in practice.

Many decisions cite several reasons against release, including the TVR, that boil down to one reason. “They say, for example, that the inmate is a foreigner and that he is at high risk of misusing his temporary release, according to the TVR, but both of these things are related to the fact that he is a foreigner. Or that he broke his last release, that he used drugs and that he has a high risk, when those three reasons are only one, because the breach was using drugs,” Amelang says.

And what do we do with the algorithm?

The TVR was presented in February 1995 in the Congress of Deputies by the then Secretary of State for Penitentiary Affairs, Paz Fernández Felgueroso. The tool was described as “gibberish” by the Popular Party deputy Ignacio Gil Lázaro. When Fernández Felgueroso clarified that the logarithms used to calculate the risk assessment would not have to be calculated by prison professionals, but by “a simple computer programme” on a diskette already in the possession of the penitentiary centres, the debate ended.

To date, the formula continues to be used to decide on temporary release, without any changes. “At the moment there is no reform process underway… But, bearing in mind that the penitentiary system is constantly evolving, it cannot be ruled out that in the future it could be carried out,” an IIPP spokesperson wrote in a statement.

Like the psychologist who developed the TVR, other corrections professionals stress the need for an update. Yela, the prison psychologist, says, “I believe that the profiles have changed, as well as the Penal Code.” Yela recalls the 1990s, when the TVR was introduced, as “the years of riots, AIDS, drugs… [prisoners] died in bunches. It was that profile of the heroin addict, whose family came from rural Spain and spent the day working while he spent the day on the street; that’s my generation, and it has changed.” Although she values the implementation of the tool at the time, Yela says that “it is no longer sufficiently useful. It’s a bit stagnant, it should be renewed if we think it’s necessary to work with it.”

García Castaño, the legal aid lawyer, argues that it is time to eliminate the TVR. “Temporary releases are given or denied on the grounds of the tables, but what is not acceptable is that one factor is worth x and with two more factors you go to a 70% risk; what there should be in the release files is an individualised assessment,” he says.

Gordaliza, the prison social educator, also thinks that IIPP should eliminate the TVR and says that the tables, like many algorithms and artificial intelligence tools: are based on statistics, so they address trends, but it will never be possible to confirm which side of the statistic a person is on.

Riscanvi, the Catalan TVR

In the 32 years since the emergence of TVR, it has taken time for a similar instrument to be implemented in Catalonia. Catalan prisons in 2009 implemented a tool called Riscanvi to decide on temporary release, also in the midst of a social panic, in this case the temporary release, two years earlier, of the rapists of Vall d’Hebron and Del Eixample. A report published last year by the Universitat de València criticised the fact that the factors analysed included whether the prisoner has low intellectual capacity, a very active sex life, a poor opinion of the government or the judicial system, or is serving their sentence a long way from home. It also found that the algorithm was particularly biased against people with few economic resources, with mental illnesses of any type, and drug addicts. Last year, the Generalitat commissioned an audit, which recommended, among other things, continuous updating of the algorithm’s factors.

Methodology

David Cabo contributed to this article by reviewing the published data. For this report we asked the Ministry of the Interior, in the framework of the Transparency Law, for the instructions issued by the General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions related to changes in the content or application of the Risk Factors Table (TVR) and the Table of Concurrence of Peculiar Circumstances (CCP), as well as data on the TVR assessments carried out in 2023 and 2024 by % of risk in which the treatment board has decided to grant the temporary release; the percentage of times that, in the high, fairly high, very high and maximum risk assessments, nationality was the only factor scored, nationality and absence of previous temporary release were the only two factors scored, and drug dependence was the only factor scored.

In its response, the Ministry of Interior provided data on the only change made to the TVR, specifically to the CCP in 1992, and argued that there is no possibility of statistical exploitation of the TVR. Civio has filed a complaint with the Transparency Council, and in its arguments the Ministry of Interior provided data on the number of temporary releases granted to nationals and foreigners, without distinguishing, as Civio requested, between EU citizens, non-EU citizens and those with or without links with Spain.

We have verified the formula and values of the variables in the Risk Variables Table with the book Validation and Purification of the Risk Variables Table in the Enjoyment of Prison Leave Permits, published in 1993 by Prison Institutions and available in print at this entity’s library.

For the analysis of provincial court decisions, between 27 and 31 January, we carried out two searches in the Judicial Documentation Centre with the terms “TVR” and “Tabla de variables de riesgo,” resulting in 151 and 161 decisions respectively, of which 38 were duplicate. We read a total of 274 decisions of which, in 250, the judicial body referred to the TVR. You can access the table with the links to these rulings here.

We developed the visualisations with D3.js and Svelte.js from prototypes in Observable, Figma and Illustrator. In the output permissions diagram, we used icons from DinosoftLabs with CC licence for Noun Project.