Apocalyptic scenarios of antibiotic resistance, but little action

The Spanish government plan against antibiotic resistance shows apocalyptic images with citizens anxiously devouring pills, but we still don’t have enough information to address the issue.

This article is a collaboration from Civio with the German journalistic organization Correctiv, which is analysing -via its Superbugs project- the impact of antibiotic resistance on citizens, and the measures being implemented internationally to stop them. It has been published in English and German.

A huge, blood-thirsty monster resembling Godzilla faces medieval warriors in a battle. At closer look the monster can be identified as a giant bacterium – so huge in fact, that later it attempts to eat the whole earth. What we are watching is not a horror film, but a video by the Spanish government aiming to warn the public on the problem of antibiotic resistance.

Earlier this year, this video was presented as part of a plan to battle antibiotic resistance. The figures highlighted in the video are no less alarming than its style. In Spain, antibiotic resistance is estimated to cost 2,500 deaths per year and 150 million euros in extra hospital costs. In 2050, if nothing is done, 40,000 people will die each year from infections that were once easily curable, according to the Government. But they don’t explain where this figures are coming from.

In Spain, as in other countries, one of the reasons leading to resistance is overconsumption of antibiotics. It is more likely that in the last two weeks a Spaniard has taken an antibiotic than an allergy pill or fever medication. Spain is the EU country with the highest consumption of antibiotics in food-producing animals (more than 2,200 tons were sold in 2013).

Troubling results like that have prompted the government to adopt a National Strategic Plan to reduce antibiotic resistance in 2014. It comes to the conclusion that the use of antibiotics seems excessive and often inadequate. And, the plan adds, the treatment is not appropriate in half of the cases.

Facts are scarce

Despite the apparent seriousness of the problem and the government’s stated intentions, Spain apparently lacks the political will for action beyond the surface: The National Plan set goals for the period 2014-2018, and included the publication of an annual report on the state of affairs, but citizens have had little information about its progress.

In 2012 the first meeting of experts on the issue was held, and it was decided to start working on the Plan. It was developed in 2013, and approved and announced in 2014. 2015 brought an update to the plan and a press release was distributed, announcing the logo. In 2016, so far, we’ve got a video.

What the country also lacks is detailed data on the issue. In 2011, only 40 percent of hospitals had tracking procedures for the use of antibiotics, according to the main document of the plan. The government has to rely on estimates and shaky data.

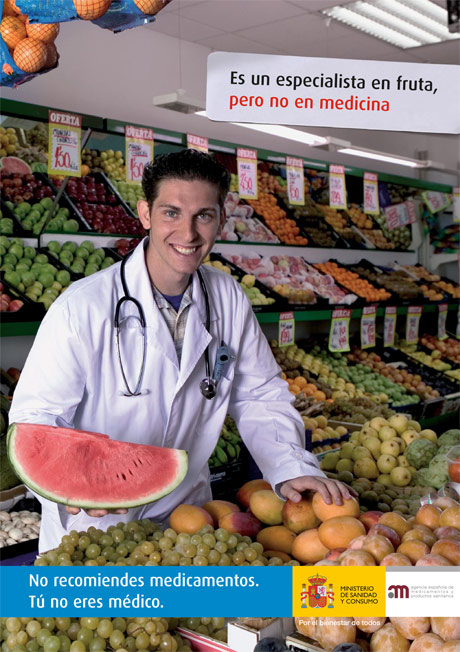

In a campaign for responsible consumption of antibiotics in 2007, the Health Ministry claimed that, although they require a prescription, 30 percent of antibiotic consumption in Spain is made without the treatment being approved by a doctor. No source was given for this spectacular percentage but, and according to newer data, the number is much lower.

Still, self-medication from leftovers at home or without prescriptions from pharmacies practicing outside of the scope of the law remains an important problem. This is shown by the 2011 Spanish National Health Survey, the most recent, interviewed 26,502 people to assess the health and health system usage of Spaniards.

7 percent of those who had consumed any medicine in the previous two weeks stated that they had consumed an antibiotic. Of these, 4 percent had consumed it without a prescription. This percentage is much higher in people aged 15 to 24, a range in which consumption of antibiotics without prescription goes up to 17 percent.

If we want more recent data we need to settle for a smaller sample. In April, a special Eurobarometer survey evaluated the use and knowledge of antibiotics by European citizens. 27,969 interviews were conducted, 1,053 to Spaniards. Among those who took antibiotics in the last year, 6 percent did so without a doctor prescription, compared to the 7 percent European average.

Half of those self-medicating got the antibiotics at a pharmacy. The other half used leftovers from previous treatments – the second highest number in Europe after Austria. Keeping unconsumed drugs for future use, or transferring them to a family member, is a common practice in some Spanish homes.

One possible solution discussed in the last years is providing less pills per package, so that there is nothing left to be stored away.

What is an antibiotic?

Misuse of antibiotics goes hand in hand with insufficient knowledge. When asked whether an antibiotic is useful to treat problems caused by virus, 46 percent of Europeans gave the incorrect answer: yes. 36 percent think incorrectly they are useful to treat fevers or colds. In Spain, these percentages were even worse – 48 percent and 45 percent.

Percentage of citizens by country who believe, wrongly, that antibiotics are effective against colds and flu

Source: Special Eurobarometer, April 2016

The only way to improve these percentages is to provide information on antibiotics. According to the same Eurobarometer, only every fourth Spaniard – versus every third European – said they had received information about the responsible use of antibiotics in the last year. Most also said they had seen it on television.

The Spanish government seems to lack the stamina in consistently informing its people. In November 2013, a public campaign was being broadcast on radio and television focusing particularly on the fact that antibiotics do not cure colds or flu. Yet the budget was much smaller than in previous campaigns: 40,026 Euro were spent on radio spots, while ads in the publicly-owned TV channels came free of cost for the Government.

In 2006, nearly two million Euro had been allocated for a similar campaign; in 2007, almost five. That year also saw a campaign aimed at cattle raisers. But, with an exception of 2011, in following years the matter no longer seemed a priority. Only in 2015, a communication budget was available again, and a very similar campaign took place, this time with a cost of half a million.

Veterinary use

Spain has a population of meat producing animals of more than 7 million tons, it in second place just behind Germany (8,749,000 tons), according to the 2014 ESVAC report. Despite being only second in the population table, it leads when looking at purchase of antibiotics: 2,965.5 tons were sold in Spain in 2014, more than in any other European country, followed by Italy with 1,441.6 tons, according to data provided by pharmaceutical companies.

The report calculates the milligrams of antibiotic consumed per kilogram of meat sold. In 2014, with a ratio of 418.8, Spain was also the leader.

Sales of antibiotics in mg of active ingredient by kg of meat, by country (mg/PCU) in 2014

Source: Sixth ESVAC Report

This data is not perfect: when we use population figures for meat-producing animals we only have estimates, and the sales data in Spain is contributed by the producers voluntarily, it isn’t mandatory. Still, they show the intensive use of antibiotics in the country. However, public campaigns haven’t targeted meat producers: We know of no public campaigns for the rational use of veterinary antibiotics, except the one in 2007.

Spain has high levels of consumption, a persistent problem associated with self-medication and a lack of control as well as detailed and reliable data on the topic, has prevented the government and the citizens from effectively evaluating and addressing the problem. But who knows – in the end, medieval knights might come to the rescue. That is at least, what the government seems to be hoping.