4 years after the hepatitis C revolution, how much do new drugs cost?

Countries with very different incomes pay similar prices for accessing the new medicines, while states continue to play along the secrecy imposed by pharmaceutical companies.

Journalists from several countries have collaborated on this report: René Ammann (Switzerland), Petra Piitulainen (Finland), Goran Lefkov (Macedonia).

In November 2014, the French government proudly announced that they had secured “the lowest price in Europe” for the purchase of Sovaldi, or Gilead’s sofosbuvir, an improved treatment to cure hepatitis C, at €13,667 for a box of 28 pills. The truth is that, at that time, the drug was just being introduced to Europe and many countries had yet to finalize negotiations, so it was easy for France to make its claim. But it was a claim that wouldn’t stand the test of time. Just two months later, Spanish government agencies were buying the same box for half the price: €7,862.5. These negotiations had been on-going for some time. The government was loathe to release the actual figures, but that is the exact amount.

In Spain, the authorities have always covered up their agreement with the lab. And they’re not the only ones: confidentiality is the norm when it comes to this type of negotiation. When Cadena Ser radio shamed the Spanish government for its lack of transparency in contrast to France’s disclosure, Alfonso Alonso stated that the cost of a single treatment in Spain was €43,500 combined with other -undisclosed- retroviral. No further details. He did also add that ‘the real price France pays is not made public’, thus accusing the neighboring country of issuing misleading information.

Hepatitis C

A disease of the liver caused by a virus, in its most serious stages hepatitis C can result in cancer and/or cirrhosis. New drugs, with almost 100% efficacy and courses of treatment lasting as little as 12 weeks, with few or no side effects, are a vast improvement on the previously available ones.

The figure Alonso stated at the time gave no indication of what was actually paid. €43,500 for a course of how many weeks? Combined with what? How much is a single box of each drug? Sometimes, however, opacity clashes with the compulsory dissemination of public procurement data. The range of purchasing bodies (state bodies, autonomous communities, health platforms within these same communities…) can help us uncover how much some of them are paying. Or to put it another way: there is no official statement at the national level, but some other public bodies are more transparent, and, whether due to their beliefs or by mistake, they publish procurement records including the clearing price per box. This price is always the same for all the entities consulted, which allowed us to publish - for the first time in 2015, and above speculation - exactly how much was being paid for Sovaldi. The price in the most recent contracts, signed in February and March 2017, was still the same: €7862.50 per box, in other words, almost €23,600 for a course of 12 weeks, the basic treatment - although many patients need a prolonged treatment to fully recover. And as the minister pointed out, these drugs are taken in combination with others.

Fetted French transparency has just been deflated. In April this year, France announced that it had negotiated a price reduction and was paying less than €28,700 for 12-week treatments with Sovaldi and Harvoni, a combination of sofosbuvir with ledipasvir, a newer drug which combines the two active ingredients in one pill. Thus, it went from giving a concrete price per box to say that the treatment with one of these two drugs, each with a very different price, is below said figure. This time the exact amount was omitted.

The story of France and Spain, the French pride when glorifying their negotiating prowess, and the accusations of lying are all examples of how this subject is being handled by governments ever since the Hepatitis C treatment revolution was sparked. Much better drugs, but much more expensive. In negotiations, the opacity imposed by pharmaceutical companies is the rule - in most countries the price paid is withheld - while, in parallel, advertisements and press releases brag about how well negotiations have gone. It’s easy to boast about having the best hand if everyone’s cards are hidden. And if the starting price of negotiations is $1000 per pill, as it was marketed initially in the USA, any price reduction is welcomed. From there on in, the percentage of discounts which are announced with great fanfare are fairly high, although the final price to pay is still extortionate, even after discounts are applied.

Italy freely admits (for example, here), that their agreement with Gilead is confidential. However the media disclosed that the agreement ranged from €40,000 to €4,000 per course of treatment, becoming cheaper with every patient treated. In Germany, also lacking an official price, Spiegel published in 2015 that the German government was buying the drug at €14,500 per box, €488 per pill, €43,500 per basic treatment.

Pharmaceutical companies claim to adjust their prices to the wealth of each country. But this isn’t always true.

As with all negotiations of this type, the pharmaceutical companies claim to adjust their prices according to the wealth of each country. But they don’t specify the figures, and in truth, this isn’t always what happens. As we discovered in Medicamentalia, countries with lower GDP are paying higher prices for their vaccines than those with higher GDPs. And the same happens with the hepatitis C drugs. Other aspects also influence negotiations, such as the size of the order or the fact that governments, without knowing what is happening around them due to opacity, negotiate in the dark.

In the case of Sovaldi, Gilead has reduced its price to as little as US$900 per treatment in some of the poorest countries. Ukraine, for example, pays €210.6 ($250) per box thanks to an agreement and purchases made via international organizations. However, in middle- or high-income countries, despite the huge differences between them, the numbers don’t add up.

Price paid by governments for basic treatment of Sovaldi

In euros and per 12 weeks treatment.

We have included only those countries for which we have official figures. Methodology.

Further to the almost €8,000 paid in Spain, the majority of countries studied pay around €40,000 for the full course of basic treatment. This figure holds true for Switzerland and Australia, but also for the Czeck Republic or Portugal. Poland pays way more: €44.000.

Following in the footsteps of the Sovaldi revolution and its associated economic benefits, other laboratories have developed advanced drugs for the treatment of hepatitis C, and competition is growing. Gilead itself markets Harvoni, a combination of sofosbuvir and ledipasvir that allows certain cases to be treated with a single pill and without combining different drugs.

Price paid by governments for basic treatment of Harvoni

In euros and per 12 weeks treatment.

We have included only those countries for which we have official figures. Methodology.

This new drug is already included in the healthcare plans of various countries. Once again, and at a price point higher than Sovaldi, the numbers soar. And in many cases, they still don’t add up. Portugal (€40,000 per basic treatment) pays more than Australia. And the Czech Republic exceeds even them, at almost €48,500. The UK pays more than €50,000. In Spain, although the government tries to cover up the exact figure, Harvoni is being purchased by various autonomous communities for €10.000 per box, around €30,000 per basic treatment. And Switzerland just got a discount and pays about €25,600.

Prices in Europe differ from one country to another but they all have one thing in common: they are squeezing the healthcare budgets of all countries that have chosen to include the treatment on their list of public services. In 2014, the EU commission approved an agreement for the joint purchase of vaccines and drugs in order to negotiate better prices and guarantee supplies. It has never been used.

Lack of access and alternatives

The first consequence of these steep prices is that some countries have chosen not to include the treatments in their public healthcare systems, such as Macedonia, where the drug has not been registered. Meanwhile, many of those who do include them have limited availability: only the most serious cases receive treatment. That’s the case in Finland, for example. In the year 2015 Finland’s pharmaceutical expenditure of sofosbuvir was over two million euros.

In June, the Spanish Ministry of Health agreed with autonomous communities to expand treatment to cover all patients. Up to that point, most were only treating the most critical cases. The same decision has just been taken by the Swiss government.

Those not included in the conditions imposed by governments to cap costs (here, for example, those of Italy) have no choice but to wait. Or search for alternatives.

Sales price in pharmacies per basic treatment of Sovaldi

In euros and per 12 weeks treatment.

We have included only those countries for which we have official figures. Methodology.

In pharmacies, prices are soaring. The laws of the market pay no heed to GDP. Italy, with a price per treatment of more than €74,000, exceeds Denmark, Finland and Norway, for example. The price for the treatment in Spain for anyone who purchases the drug with, for example, a private health prescription, is €44,000.

Some patients opt to travel to countries where treatment is cheaper. Such is the case with the so-called buying clubs created in Australia, for example, to buy the pills from India, where production of much more affordable generic versions is allowed.

Health tourism

Another option is to combine a few days visiting the Pyramids, 5 star hotels and treatment. All with the blessing of Messi. Egypt, the country with the most cases of hepatitis C in the world, has a lower price for such treatments, thanks to agreements with Gilead and the use of generics.

Leo Messi endorses a tour which includes hepatitis C treatment | Tour n’ Cure

Two labs in the country have taken advantage of the Western price bubble to offer what they call Tour’n Cure, a trip to Egypt that includes diagnosis and the first days of treatment. The rest of the pills go back home with you in a little box, along with the jars of desert sand, and the pyramid-shaped souvenirs. Besides offering curative holidays to those who can afford them, the organization combines profits with a veneer of social charity: a free treatment donated for every 1000 followers of its cause, according to its website, vouched for by sporting stars such as Leo Messi or Dani Alves.

The Spanish version of the same package holiday is offered by Sanantur, a travel agency that charges a minimum of €5,419 for a 5-day holiday plus full treatment. The same agency can take you to Istanbul for a hair transplant.

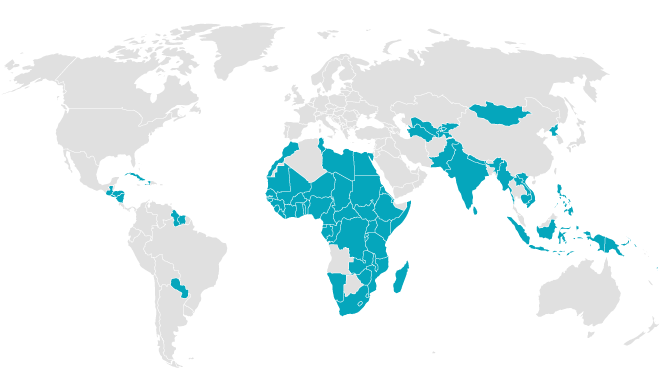

Egypt was in fact one of the first countries to reach an agreement with Gilead to produce their own generic treatments. In India, the company also signed voluntary licensing pacts with 11 pharmaceutical companies allowing them to develop and produce sofosbuvir and other derivatives in exchange for 7% of profits. The agreement features plenty of small print however: the signing labs can export their low cost version to 101 countries listed in the conditions (15 of which are small island nations), but the rest are excluded. Countries such as Brazil, China, Mexico, Turkey, Thailand or Morocco have been vetoed from the list of possible recipients of the generic Indian drug.

The 101 countries that can buy the generic Indian drug

According to the WHO, 71 million people around the world suffer from hepatitis, and a large number of these develop cirrhosis or liver cancer if not treated on time. Around 399,000 people die from the disease every year.

Of the total affected number, 85% are in countries with low (73%) and medium incomes (12%). Despite this, R&D efforts have focused on the genotypes of the virus which predominate in high-income countries, as decried by the organization DNDi (Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative), which has initiated a project to combine different drugs and create an oral treatment, one which is safe and accessible, as well as suitable for all genotypes.

Farmanguinhos, the Brazilian state-owned laboratory, has come out against the Sovaldi patent. ANVISA, the National Agency for Health Vigilance (Agencia Nacional de Vigilancia Sanitaria) has followed suit, as has the Brazilian government itself. While they wait for the patents authority to make its decision, the laboratory has announced that, if the patent is denied, Farmanguinhos may produce its own drug in conjunction with a national business conglomerate. This is not the first time that Brazil has gone head to head with the patents system in situations where treating all sufferers with a new drug would blow a hole in the country’s public healthcare budgets. They already did so in 2007 with an antiretroviral, efavirenz, when they approved a compulsory license allowing them to avoid the patent and produce their own version. And it went pretty well.

Methodology notes

Most countries conceal the price paid to buy these drugs in order to preserve confidentiality agreements. Nevertheless, we have managed to obtain data for some of them. To uncover the prices paid by different governments for Sovaldi and Harvoni, we have used - whenever possible - public procurement records for completed purchases. These are the most reliable source and served us in the cases of Spain and Portugal. In other cases, we use the price that countries pay for reimbursements, or official press releases. These figures are less reliable since the labs can offer significant discounts for large volumes when it comes to finalizing payment. We have only used this method where we know the factory price, without taking into account marketing costs or tax. This is the case for Switzerland, the Czech Republic, Ontario (Canada), Poland, Australia, UK and Ukraine. Regarding sales prices in pharmacies, we used official bulletins and the final sales price, i.e. what a consumer pays. For more information, please contact us.