Medicamentalia, Best Investigation of the Year in the DJA 2016, behind the scenes (part I - for journalists)

This is the first post of a serie about how we made Medicamentalia.org, a global investigation about access to essential medicines that won the ‘Best Investigation of the Year‘ (small newsroom) in the Data Journalism Awards 2016

Early research

The task of understanding something as complex as the international regulations and rules affecting the prices of medicines is colossal. So we want to thank those who helped us through some early conversations, either face to face or by telephone, email or videoconference, to know what and how to investigate. Elisa Lopez Varela, doctor at the Medical Research Center in Infectious Diseases in Mozambique; Elisa Sicuri, health economist at IS Global in London; Judit Rius, US director of the Campaign for Access to Essential Medicines of Médicins Sans Frontières in New York or Margaret Ewen, responsible for the HAI database in the Netherlands are some of the many expert we conducted interviews with. Their input was key to help us focus this investigation. We didn’t think even remotely that we were the first to face this issue and wanted to learn from those before us. In this sense, the experience of initiatives such as Medicamentos Abiertos, in Central America, or the fantastic project of Code for South Africa was very useful.

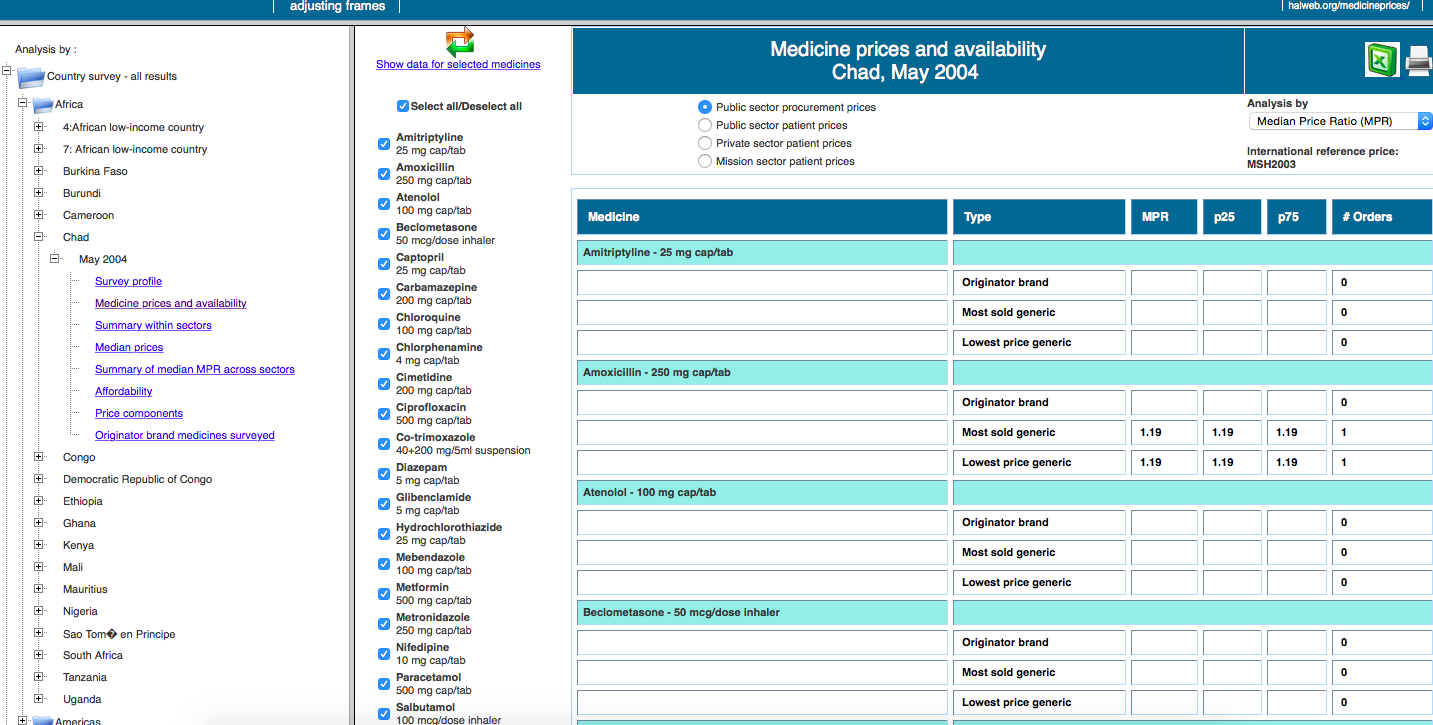

For weeks, we looked for a common standard through which we could compare, in the most rigorous way possible, the accessibility to treatments in different countries. That’s when we discovered the cornerstone of the project, the database developed by the not-for-profit Health Action International (HAI). Thanks to an exhaustive and detailed methodology, which we studied thoroughly to understand the complexity of the data, they’ve managed to collect information from dozens of countries worldwide on pricing, access, differences between brand name drugs and generics, cost composition … of 14 essential medicines in specific compositions: diazepam, paracetamol, cotrimoxazole, atenolol, glibenclamide, diclofenac, ceftriaxone, captopril, amoxicillin, amitriptyline, ciprofloxacin, omeprazole, salbutamol and simvastatin.

The database

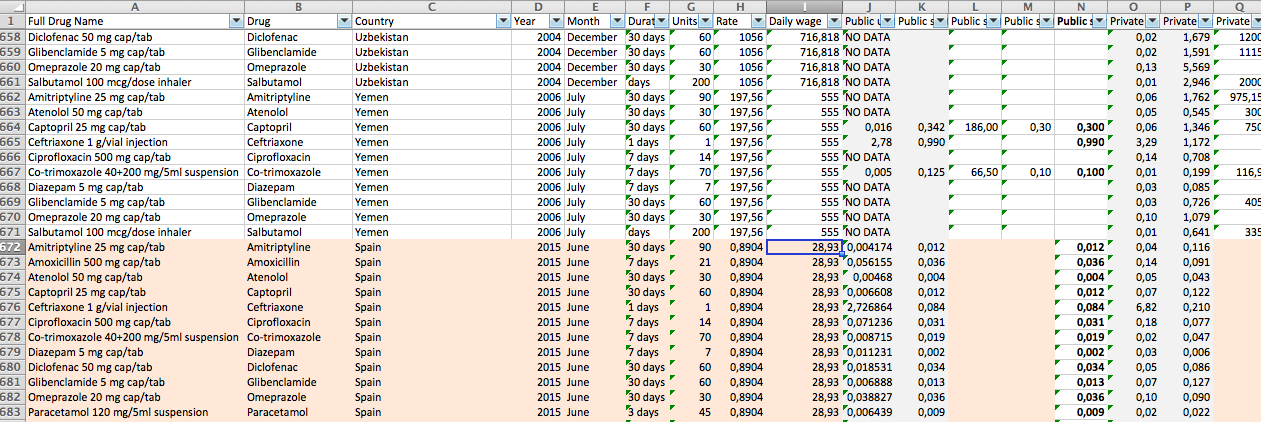

The first obstacle to our research, aimed at comparing countries of different regions and income, was that studies of HAI were dated in different years. Although we considered updating all the figures to 2015 (taking into account inflation and currency rates’ changes), we eventually decided that the comparisons would be inaccurate if we used absolute data. That’s the reason you won’t find prices in our data visualization.

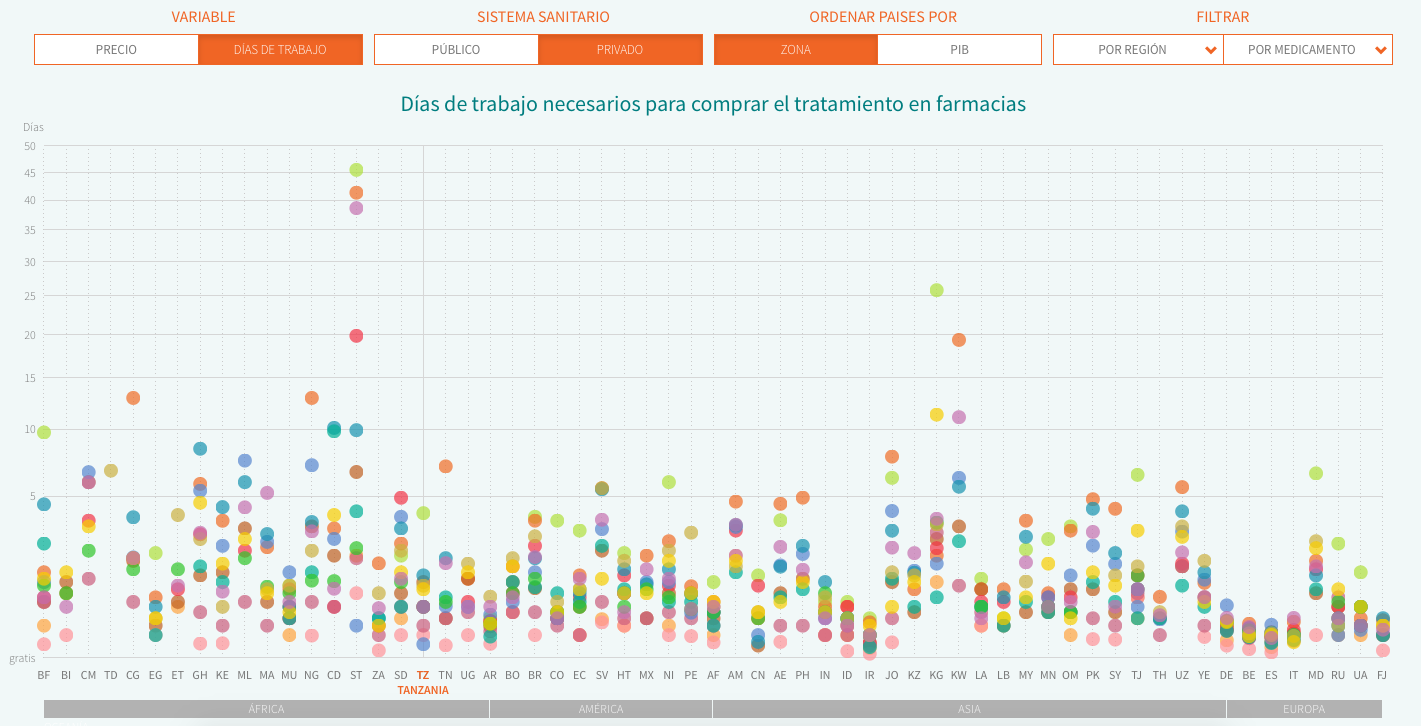

Thus, we decided to use two relative indicators part of HAI’s reports: MPR (Median Price reference), the ratio of the drug price versus an international reference value set by the not-for-profit organisation MSH. We can compare the deviation across countries from this reference price, which is updated every year. The second indicator we analyse is affordability, i.e. the work time needed to pay for a full treatment in each country, using the net salary of the lowest-paid public servant (as specified by HAI’s methodology in order to avoid more volatile figures in developing countries). In both cases, we decided to do the analysis using the price of the cheapest generic and display both private (direct purchases in pharmacy counters or with prescription from private insurers) and public data (purchases subsidised partially or fully by public health systems).

With our goals now clear, on March 11 we downloaded about 70 documents from HAI’s website, and processed them automatically to build a working database. We then filled the gaps, cleaned, restructured and checked all the data, either automatically or manually. That way, we had set our base camp: we had data from 56 countries for 14 essential drugs. Having understood the methodology and cleared up some doubts thanks to Margaret Ewen (HAI), now came the second part: add data for developed countries to carry out the global comparison. We did it through official sources and after a study of the public health systems of each of the five included countries: Italy, Argentina, Spain, Belgium and Germany. In all these cases, we used data from 2015 and the latest available international reference price, 2013, just as is done in HAI’s studies. In the German case, the team at Correctiv! collected the data and we fact-checked it to ensure everything was accurate, as was the case.

The process of gathering the price data has varied depending on the contribution of the public administration in each country. In our methodology you will find step-by-step how and where we gathered data form countries like Italy, Argentina, Spain, Belgium and Germany.

The final database includes data from both HAI’s reports and these four countries, and you can download it here. We have visualized it (sorting the countries by name or GDP) using Javascript and D3.js. You can find the web source code here.

Reporting from the field

In Civio we know well that data alone says absolutely nothing. Analysing the database allowed us to draw some interesting conclusions, but the background information and explanations or consequences of the problems of access to medicines were left out. From the beginning we knew we needed reports from the field. To this end we traveled to Ghana to cover the problem of malaria and counterfeit medicines.

And to Brazil, to learn about compulsory licensing, an alternative to patents used in that country in 2007. We also researched the patent system and its alternatives, since the 14 drugs considered essential by the WHO are available as generics, and we didn’t want to leave aside one of the major debates on access to medicines worldwide.

This research was important, as it examined one of the major debates on access to medicines: is the patent system the best way to compensate for investments in the drug’s development, and, at the same time, ensure access to medicines for everyone? This background information was essential to prove that the costs of creating a new drug are not transparent. We found that although the pharmaceutical industry acknowledges the benefits of some alternative models to intellectual property in very particular cases, the patent system is non-negotiable. We also found out that the 2007 approval of compulsory licensing in Brazil didn’t make drug companies abandon the country, as was augured by certain companies and governments. Quite the opposite, both foreign investment and the number of patents have kept growing since then.

With this background, we published three multimedia features about patents, counterfeits and the compulsory license with video interviews and animated infographics.

The journalists involved were:

- Eva Belmonte. Journalist. Original concept, project lead, research, data gathering and analysis, and fieldwork in Brazil.

- Miguel Ángel Gavilanes. Journalist. Research, data gathering and analysis. Video editing and coordination.

- Antonio Villarreal. Journalist. Research, fieldwork in Ghana and editing.

And a great list of contributors:

- Anne Vigna. Video and photography in Rio de Janeiro.

- Elio Stamm. Vídeo in Ghana.

- Joseph Akwasi. Photography in Ghana.

- Henry Souza Nelson. Photography in Ghana.

- Marta Silvera. English translations.

- Jen Bramley. English version editing.

- Fabiola Czubaj (La Nación) helped us understand Argentina’s data.

- Belinda Grasnik (Correctiv!) gathered the data for Germany.

- Kristof Clerix (Knack) gathered the data for Belgium.