Only three out of ten ambassadors from European Union countries are women

Finland is the only EU country with a female majority while at the other extreme, in Italy and Czechia, men dominate the diplomatic corps.

Becoming an ambassador is the pinnacle of a diplomatic career, a destination reached after years of study, major outlays of resources and sacrifices. At those rarefied heights, the persistent inequality among ambassadors is hard to ignore: men far outnumber women. Even with equality policies in some European Union (EU) countries, females averaged only around 30% of all EU ambassadors in 2024. “Diplomacy has traditionally and formally been a domain reserved for men only,” write professors Karin Aggestama and Ann Towns in the International Feminist Journal of Politics.

The reasons behind these figures are as numerous as they are complex. Deborah Rouach, co-director of the Institute for Gender in Geopolitics, explains one of them: “To explain the low proportion of women in high-level positions or ambassadorial posts, it is necessary to take into account the fact that women entered the diplomatic service late, around the 1970s.” There are countries that did not see a woman at the head of an embassy until relatively recently. Greece, for example, did not appoint its first female representative abroad until 1986, when Elisavet Papazoi took over the embassy in Cuba. Portugal took even longer: Maria do Carmo Allegro de Magalhães became its first female ambassador to another country – Namibia – in 1998. However, Maria de Lourdes Pintasilgo had already paved the way in 1975 as Portugal’s ambassador to UNESCO, before becoming the country’s first and so far only woman prime minister.

In some EU countries, there was an explicit ban on women entering the diplomatic service. This was the case in Italy until the 1960s and in Spain between 1941 and 1962 during the dictatorship, when one of the conditions for the entrance exam to the Diplomatic School was “being male.” However, prior to this period, Spanish diplomat Margarita Salaverría had already passed the competitive examination for the diplomatic service, and the government during Spain’s Second Republic appointed Isabel de Oyarzábal ambassador to Sweden between 1936 and 1939, making her one of the first female ambassadors in Europe.

More than 70 years after the first female ambassadors, there are still EU countries with minimal female diplomatic representation and the gender gap persists year after year. Ann Towns, professor of political science at the University of Gothenburg, says that progress in this area “is surprisingly slow” and adds: “It has come very late, and that surprises me a little because, given the nature of diplomacy, diplomatic interactions and bilateral diplomacy, I don’t see why it should be an area where women would have difficulty entering.”

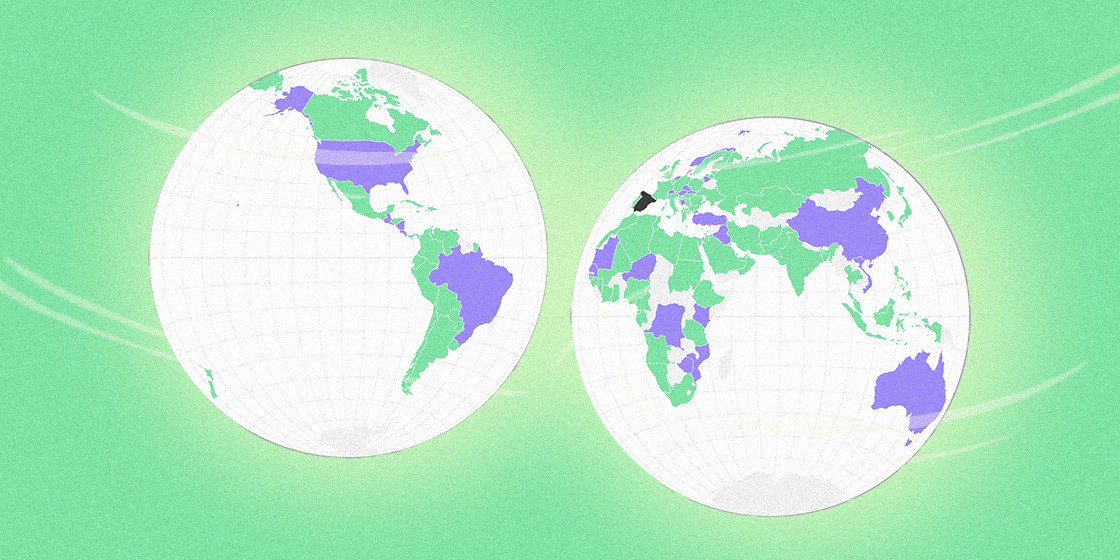

Both globally and within the EU, the proportion of female diplomats has risen, although the absolute percentages remain very low. In 2024 the global average reached 23%, while the EU countries reached 30%, seven points ahead, according to University of Gothenburg’s project GenDip. However, not so long ago – in the early 2000s – neither average exceeded 9%. If we go back even further, to 1968, the first year for which records exist, the presence of women in embassies was less than 1%.

The reasons behind the current situation are different from the prohibitions imposed in the past, but many of the social pressures that prevent women from accessing positions such as ambassador continue to follow a traditional pattern. “The entire diplomatic structure – or the very idea of being an ambassador – has historically been based on the figure of a male ambassador with his wife and children, right? The wife helps him in his work. She collaborates in all the representative aspects: organising receptions, lunches, cocktail parties and dinners, which are a very important part of an ambassador’s role. But when it comes to female ambassadors, they don’t necessarily have the same support from their husbands, because husbands are not usually willing to take on the exclusive role of ‘husband’. They are not going to devote their time to organising dinners or performing those kinds of tasks,” Towns says.

The problems are even more glaring when we compare the paths of large numbers of diplomats. A study by Politic Science’s professors Romain Lecler and Yann Goltrant on french diplomats concluded that the main difference between the two genders was the amount of time they had spent abroad, with women five times more likely to take leave during their careers and twice as likely to avoid all international assignments. Women also travelled to destinations closer to home. Perhaps as a result, Lecler writes, female diplomats were half as likely as their male counterparts to attain high-ranking positions.

Spanish career diplomats reported similar experiences when the Spanish Court of Auditors asked them: for most women, family responsibilities weighed more heavily than for men. Most career diplomatic staff also believe that gender affects ambassadorial assignments. Some 68% of women surveyed said that their gender hinders their access to ambassadorial positions. In contrast, 76% of men said that being a woman helps.

Parity is close for some and distant for others

There was only one EU country with more female ambassadors than male ambassadors in 2024: Finland. Of 73 ambassadors, 39 were women and 34 were men. Ireland was close behind, with almost half of its ambassadors being women. At the other end of the spectrum, Cyprus, Malta and Czechia did not even reach 15% female representation. In the middle were countries such as Belgium, with 15 female ambassadors, which translates into a 17.6% female presence.

These percentages are particularly interesting in countries with a large number of diplomatic missions around the world. Within the EU, there are five countries with more than 100 ambassadors: France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and Italy. In 2024, the Netherlands almost achieved parity in its envoys, while the rest were close to the European average in terms of female representation. Except for one: Italy.

If we look closely at the data from recent years on Italy’s foreign representation, the presence of female ambassadors is minimal. Between 2014 and 2024, according to figures provided by Openpolis, there have been no more than 20 women in this position in any given year out of the more than 100 missions it has around the world. Specifically, in 2016 and 2017, there were only seven female heads of mission out of an average of 120 envoys in those two years.

In addition to equality, there is another important factor, which is the importance of the country to which the representative is sent. Towns, who conducted research using data from 2014, explains: “If you look at the most important posts – the most relevant economic capitals or key destinations in military terms, those of the superpowers and very rich countries – women are under-represented in those destinations. There is an overrepresentation of men.” If we look at representatives in G20 countries, Italy, for example, had only four female ambassadors in 2024: in France, Korea, Russia and the United States. Poland and Belgium had only male ambassadors to the G20 in the same year.

Changing the rules

There are other ways to become an ambassador. In Spain, for example, former prime minister Felipe González appointed ten ambassadors without a diplomatic career and his successor, Jose Luis Rodríguez Zapatero appointed 11 during their terms in office. Even Isabel de Oyarzábal was a political ambassador. For career diplomats, it takes years and years to reach the top: “It can take 20, 30 or 40 years,” says Lecler. The good news is that there are more and more women in the diplomatic service. According to the Association of Spanish Women Diplomats, 2021 marked a milestone: for the first time there were more women than men in that year’s incoming class. It happened again in 2022, and in 2023 the number of women and men who passed the entrance examination was the same.

In other countries, the proportion of female diplomats has also increased considerably: in France, for example, it rose from around 8% after the Second World War to more than a third in the 2010s; in Sweden, it rose from 4% in 1971 to more than half in 2014. Now, the next step is to break down this difference in management positions, Towns says: “The career path is a leaky pipeline. The women drop off, and I guess it is because of the accumulation of different factors, so it is a little a bit like dying from a thousand paper cuts”. Rouach adds: “All professional careers should be fully open and suitable for women, regardless of whether they have children or not. Therefore, it is necessary to rethink the exercise of power and, above all, to destroy the glass ceiling that exists in these careers. Until this is done, it is true that it will continue to be a field only suitable for men who can count on their wives to take care of the family.”

Methodology

Collaboration

This article was produced in collaboration with the media outlets Openpolis (Italy), Le Soir (Belgium) and Dataninja (Italy).

The interview with Deborah Rouach was conducted in French by Agathe Decleire and translated into English.

Within Civio, Ter García participated by reviewing data and Eva Belmonte by editing the article.

Methodology

This article is based on an analysis of data collected by the GenDip project at the University of Gothenburg. The data used is from the August version, which covers the genders of ambassadors around the world between 1968 and 2024, although it does not cover every year. The GenDip project classified the ambassador of each mission in autumn 2024, so there may be variations between this and other databases or changes in the ambassador before or after that date.

The gender categorisation in the database is only “male” or “female”, based mainly on names. While some diplomats may have other gender identities, unfortunately, they are beyond the scope of this work.

From the data, we selected those under column number three, ‘title’, which refers to those with the rank of ambassador. We have excluded from our analysis any other type of position such as ‘Chargé d’affaires’ or head of business. In the EU countries for 2024, there were 159 additional records to those included in the analysis, which may contain, for example, interim staff in the position of ambassador at the time of data collection.

Furthermore, the downloadable GenDip dataset only includes embassies where the ambassador resides. Therefore, we can only refer to the number of ambassadors, rather than the number of countries, since some embassies serve more than one country.

We checked the data for the countries relevant to this article. We compared the names and gender of the ambassadors in 2024 from Germany, Spain, Italy, France, and Belgium with those from GenDip. We found that the database categorised the Italian Ambassador to Senegal in 2024 as male when official sources identify her as female. We also found that, at the time the data was extracted, the French Embassy in Spain had an interim ambassador, who did not appear in our records. We have therefore changed this to include the ambassador who was in office for the first seven months of the year before leaving the post.

For Italy, we have combined data from GenDip with that provided by Openpolis. This gives us the evolution of the percentage of female ambassadors per year. It should also be noted that there are certain differences regarding the positions held by five heads of mission. According to Openpolis and the official website of the Italian Ministry, the embassies in Accra, Baghdad, Pretoria, Bangkok and Tashkent are headed by Chargé d’affaires rather than ambassadors.

Regarding the visualization showing some of the first female ambassadors from European Union countries to other countries, the sources are as follows: Spain, Bulgaria, Denmark , Sweden, Finland, Austria, France, Ireland, Belgium, Hungary, Italy, Greece, Latvia, Slovenia, Lithuania and Portugal.