Spanish National Police stop using Veripol, its star AI for detecting false reports

The Ministry of the Interior states that they have rejected its use because it is not valid in judicial proceedings.

“It is the first tool of its kind in the world,” the National Police wrote in 2018 when it presented Veripol as an algorithm capable of detecting false reports of robbery with violence, with an accuracy of more than 90%. In October 2024, six years later, the National Police stopped using the AI, the Technical Office of the Directorate General of Police has told Civio. The Ministry of the Interior stated that the reason for rejecting its use is that it lacks validity in judicial proceedings.

The abandonment of Veripol comes three months after the publication in Spain’s Official State Gazette (BOE in Spanish) of the European regulation on artificial intelligence, which includes polygraphs among “high-risk” AIs, which have stricter requirements for review, updating and transparency. In late September 2024, a University of Valencia report by legal and mathematics researchers pointed to serious shortcomings in the tool. The first of these is the lack of information about how it works.

Researchers from the Complutense and Carlos III universities, and the police officer Miguel Camacho-Collados, currently responsible for technological innovation and cybersecurity at the State Council, developed Veripol. As the academic article detailing its development explains, the team trained the tool on a sample of 1,122 reports of theft in Spain in 2015, of which 534 were true and the remaining 588 were false. The researchers processed the texts of the reports with NLP techniques, simplifying them to be processed automatically, and classified the words used by type, discarding all those that appeared in less than 1% of the sample or in more than 99%. They then applied various statistical regression methods to choose which words were most common in true and false claims. As an example, if a report contains the words “day,” “lawyer,” “insurance,” or “back,” it is more likely to be false, Veripol predicts, and even likelier to be false if the report contains the words “two hundred” several times or adverbs such as “barely.” Conversely, reports that refer to buses, a particular make of mobile phone or a car number plate are more likely to be true.

In June 2017, the Veripol team conducted a pilot test in police stations in Malaga and Murcia. According to the academic article, in 83.54% of the reports identified as false by Veripol, the complainant ended up confessing to lying. In December of the same year, the Spanish Police Foundation gave the research an award, and in 2018 the Ministry of the Interior announced its implementation in all police stations.

According to data from Algorithm Watch, from its implementation until October 2020, the National Police used Veripol to analyse around 84,000 complaints. Of the 49,702 complaints police analysed with Veripol in 2019, the police concluded 2,338 were false, using a combination of Veripol and other means. In 2022, police used it far less, the University of Valencia report states: the number of complaints police analysed with Veripol fell to 3,762, of which police determined 511 to be false.

The report points out serious deficiencies in the tool, starting with its approach: the basic idea that 57% of the reports of robbery with violence that are presented are false, a figure that has as a reference point the high number of unsolved robbery cases. It also criticises the small sample of just over a thousand complaints compared to the approximately 60,000 cases of robbery with violence that are registered each year in Spain, according to the Crime Statistics Portal. It also notes the lack of a protocol and of information on police officer training for its use. Vigo police station, which had been using the programme since 2018, was later unable to use it due to a lack of training for its officers, La Voz de Galicia reported in 2020. The complaints analysed by Veripol were actually written by police officers, so it is not a literal reproduction of the complainant’s statement, the Valencia report states: “It does not analyse the story that the potential liar is telling the police, but analyses the story that the police officer writes himself.” The tool also fails to take into account language differences across Spain.

“The system is not transparent,” the University of Valencia researchers write: “There is no official data available on Veripol at all.” In February 2023 and again in December 2024, Civio requested information on the technical functioning of Veripol and its use, but to date the Ministry of the Interior has not even reported the number of police stations that used it.

Methodology

In February 2023, Civio requested from the Ministry of Interior the technical specifications of Veripol, its use cases and any other document that allows us to know how the application works and what information it contains or may contain. Faced with the refusal of the Ministry of Interior to provide this information, we filed a complaint under the Transparency Law with the Council for Transparency and Good Governance, which on 31 October of the same year ruled in favour of our right to the information and ordered the Ministry of Interior to provide the requested information. The only information finally provided were the links to the press releases published by the Police and the Complutense University on its implementation and the prize awarded by the Spanish Police Foundation.

In December 2024, Civio again requested information related to Veripol. Specifically, we requested the list of police stations that had implemented the tool and their usage data, including the number of cases processed per year and the percentage of cases in which the tool had concluded that the complaint was false. The Ministry responded by stating that they had stopped using Veripol on 21 October 2024 and refused to provide usage data. Civio filed another complaint with the Council for Transparency and Good Governance to access this data, which is still pending.

David Cabo and Ana Villota participated in the genesis and implementation of the game.

In the pre-print of the article published in the journal Knowledge-Based Systems, “Applying automatic text-based detection of deceptive language to police reports: Extracting behavioural patterns from a multi-step classification model to understand how we lie to the police” (Lara Quijano-Sánchez, Federico Liberatore, Jose Camacho Collados and Miguel Camacho-Collados, Cardiff University, 2018), we find data from 2015 on the tool, as well as a list of 110 terms, translated from Spanish to English. We have contacted the authors, but they have not provided us with the original list of words in Spanish.

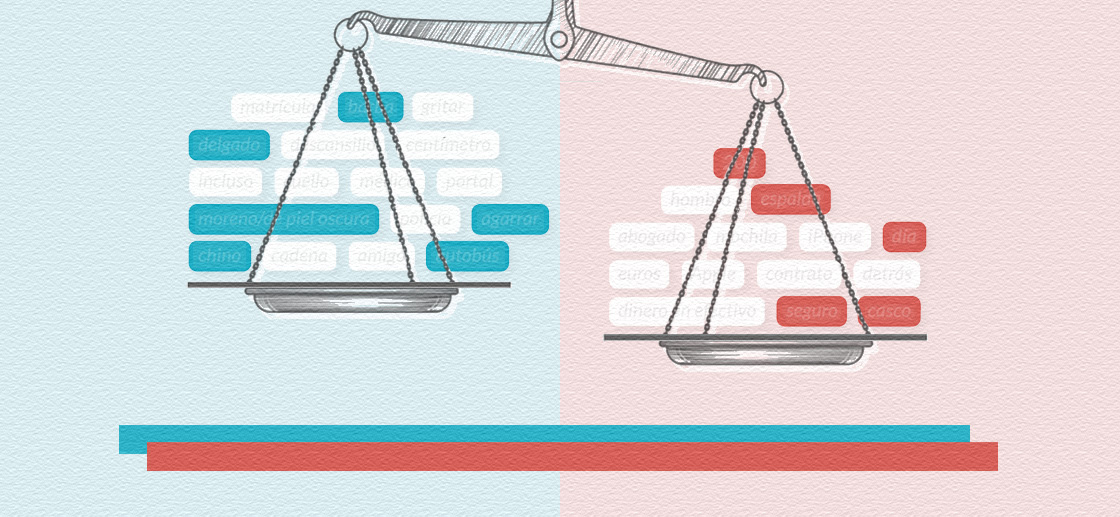

Therefore, to avoid ambiguities arising from translation, we have included only those words that are explained in context. The final list of terms, with their respective weights (the higher the value, the greater the influence), of words which, if they appear or appear very frequently, determine that the report is probably false are: day (0.48), lawyer (0.43), insurance (0.24), back (7.74), backpack (0.10), shoulder (17.99), helmet (26.92), iPhone (25.56), Apple (0.23), barely (0.19), behind (0.12), two hundred (0.30), euros (6.81), cash (19.18), contract (19.19).

The selection we made for the probably true cases is: bus (0.52), number plate (0.19), chain (16.06), police (0.31), Chinese (52.58), neck (16.62), portal (0.26), landing (0.36), even (72.31), beard (0.34), centimetre (0.09), thin (0.09), dark (0.10), shout (40.67), grab (0.12), doctor (16.75), friend (0.13).

We developed the visualisation of the game with Svelte.js.