Spain, Czechia, Denmark and Belgium are the meccas of reproductive tourism

Barriers in many European countries push thousands of people abroad to access assisted reproductive technology (ART) techniques. In some cases, they take out huge loans to pay for the treatments.

When Marie and her partner failed to conceive a baby for almost a decade, they ran into a wall. “We did a [gamete] donation procedure in France that didn’t work,” she says. At the same time they had to face another problem: the wait lists for assisted reproduction were two years long. “And when it doesn’t work, you have to wait another two years,” Marie points out. The delays made them fear the worst: ageing past the limit of 45 years old that France imposes on women for accessing ART. “If you can financially handle it, you’ll go to another European country which has the same assisted reproduction procedures, but faster,” she explains.

Marie, who traveled to Spain, is not unique. Erika (who, like Marie, uses a pseudonym in this story at her request), a Hungarian woman who has been trying to conceive with her partner since 2017, is also seeking access to egg donation. Although egg donations are possible in Hungary, the government requires the donor to be a family member. “I don’t have a relative who can donate an egg,” Erika says. This was the main reason that led her to cross the border to Slovakia, but the saturation and dehumanisation of the Hungarian health system also contributed, she says: “We feel like we are guinea pigs. We are primarily motivated to be treated as human beings and not to be like what we feel in Hungary to be put on a conveyor belt. Specifically, you didn’t even put on your pants, but the doctor was already on another patient.”

Sperm also travel

“A friend who is an embryologist told me they often had Danish donors at her clinic and I watched a programme called The Vikings are Coming about Danish sperm, so Denmark seemed to be a good place to start,” says Liv Thorne, who recounts her experience as a single mother in a recent book. She obtained donated semen in Denmark and had it sent directly to the UK. Why? Lack of supply: “In the UK it is not something that men commonly do, to donate sperm,” she explains to Civio. It is not the only country with supply problems: in Italy, according to 2018 data, 96.8% of imported sperm came from Spain, Denmark and Switzerland. “Transporting semen is relatively simple because a sperm sample spoils very little when freezing and thawing,” says Iñaki González Foruria, a specialist at the Dexeus Mujer fertility clinic. The same does not happen with egg donation since they are much more sensitive to freezing and many other factors. That makes it difficult for them to be kept in good condition in transport, so many people have to go abroad to obtain donated eggs.

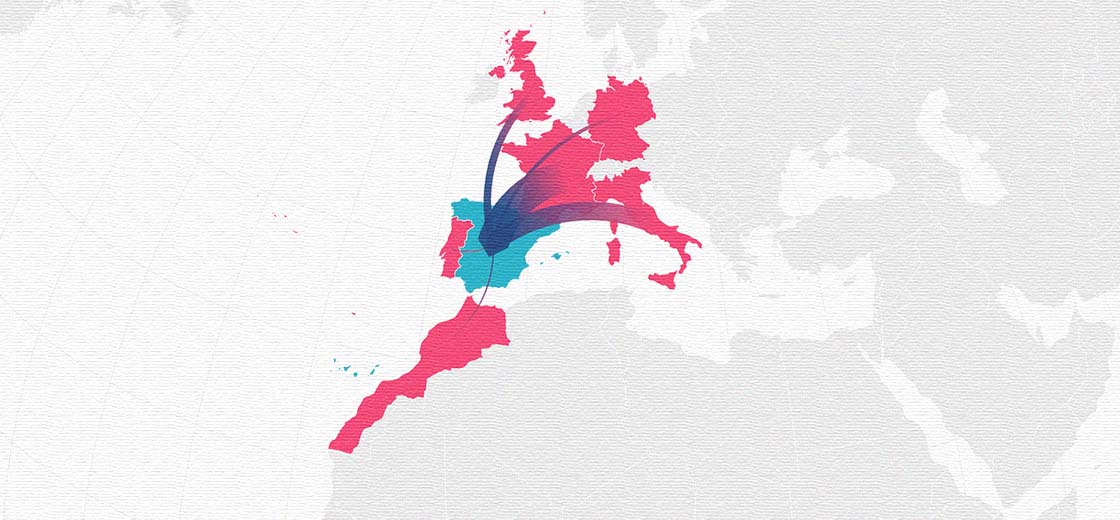

A recent study reported that some 5% of European fertility care involves crossborder travel. The most popular European destinations are Spain, Czechia, Denmark and Belgium. In 2019, for example, Spanish fertility clinics carried out 18,457 treatment cycles for people from abroad, the majority from France and Italy, while Denmark performed more from 8,000 treatments for international patients, 21.69% of their total. In Belgium in 2018 13 out of every hundred cycles of in vitro fertilisation was for patients living outside the country, mostly other European Union member states. In contrast, in Lithuania between 2018 and 2020 the Ministry of Health counted only ten non-residents, most from Russia and Belarus, seeking ART.

What do people seek in each country?

The people Civio interviewed are a small fraction of the millions of users of assisted reproductive technology -some eight million babies have born thanks to these techniques— but for one reason or another they have felt forced to pursue ART far from home. The most common reasons are the multiple legal limits imposed in their home countries. Half of European countries prevent female couples from accessing ART and almost a third extend the ban to women who are single by choice. But there are also other barriers, such as age limits or the number of cycles financed. Other reasons include the long waiting lists, as in France, the need for higher quality or cheaper healthcare and sometimes a desire for anonymous donations.

In countries such as Hungary, where LGTBIQ+ couples are prohibited from using ART, foreign fertility clinics advertise their services to potential users. “In Czechia, in Ukraine and later in Austria, we could see that new institutions began to advertise for Hungarians in Hungarian just offering their services basically at the same price or very similar prices to the whole Hungarian private [sector],” says Bea Sandor, spokesperson for the Háttér Society. For Marie and her partner, language was not a barrier when they moved to Spain: “I don’t speak Spanish. But for French people it’s really easy. [Clinics that] take care of French patients speak French,” she says. According to gynecologist Marisa López Teijón, director of the Institut Marquès fertility clinic, her international patients “come from more than 50 countries.” It is also common for the most renowned clinics to open locations abroad.

Those who travel abroad in search of assisted reproduction choose where they will go according to their needs. This is what happened to Marie: “I live in Toulouse. It’s three hours away from Barcelona,” she says. Both Spain and Czechia are common destinations for people who have fertility problems and require donated eggs, as in her case. The data are overwhelming: 54.3% of treatments started in Spain in 2019 in foreign patients involved egg donation. The figures are also striking in Czechia: in 2017, the egg donors were residents (99.7%), while the recipients were mostly foreign people (86.3%).

More than half of donor inseminations in Denmark were made to foreign persons

In contrast, Denmark is famous for its sperm donors. In fact, according to the Danish Health and Medicines Authority, 55.5% of donor inseminations in Denmark were for foreign recipients. “Denmark is a relatively open country when it comes to sperm donor legislation,” says Lasse Ribergård Rasmussen, spokesperson for Cryos International, one of the most famous sperm banks. From their headquarters in Copenhagen -together with centres located in Cyprus and the United States- they send samples to 100 different countries worldwide. “Long waiting lists and legal aspects in the customers’ respective countries are also factors that can affect their decision,” Rasmussen says.

Loans to pay for treatments

Crossing the border implies, in most cases, a significant financial outlay. “Save every penny. Fertility treatment is very expensive,” Thorne says. Erika traveled to a clinic in Bratislava, Slovakia, instead of neighboring Czechia, to save money: she and her partner paid 4,000 euros for treatment, using a bank loan, instead of the 6,500-7,000 euros that they would have to pay in a Czech clinic. For her part, Marie estimates an expense of some 9,000 euros, counting the treatment and the three trips between Toulouse and Barcelona. “You have to be able to handle it,” she acknowledges.

Although the reasons for traveling to each place vary, all these countries have something in common. Permissive legislation and high success rates seem to have made them attractive destinations for thousands of people.

“Spain’s law, despite being older, has a very good permissiveness. The centres have been organized very well, they have achieved very good results, circuits and a way of functioning,” says González Foruria, the Dexeus Mujer gynecologist. “Spain, both in egg donation and freedom and having more facilities is one of the leaders in Europe”, says Juana Crespo, founder of the eponymous fertility clinic.

In the case of Czechia, according to the Institute for Health Information and Statistics, the reasons for this are similar: open legislation, the broad availability of anonymous donors and the quality of treatment. “Czechia is a popular IVF destination especially because it can offer both high success rates and affordable prices,” says Michaela Silhava, director of the Unica Clinic in Prague, Czechia. Most of his patients come due to legal restrictions, such as those in Italy, Germany and Austria, or because of long waiting lists, as in the United Kingdom.

However, the health authorities of Czechia fear that the arrival of too many international patients could make it difficult for those who live there to access assisted reproduction. This is clear from the 2017 report published by the Institute for Health Information and Statistics. The document warns of the risks of price increases and that ART treatments may become less accessible to residents of Czechia. Yet fertility specialists in Spain rule out that this could happen there because egg donation is also frequently used by people residing in the country and due to the competition between private clinics. As of publishing time, Civio has have not received a response on this matter from the fertility clinics contacted in Czechia.

What about the future?

An important question is whether the discrimination that still affects many people will end in the future. It is no longer just a question of access, but also of avoiding any type of subsequent exclusion. Like the one suffered by Chiara Foglietta and Micaela Ghisleni, a couple of Italian women who traveled to Denmark for artificial insemination. In April 2018, their son came into the world, as Foglietta, a Turin city councillor, wrote in a Facebook post. But, when registering him in the Civil Registry, the officials asked her to lie, to say that she had slept with a man. “There is no formula to say that you have done medically assisted reproduction,” Flogietta wrote.

Although they finally succeeded in registering the baby as the first registered child of two mothers in Italy, their experience is common. In Ireland, female couples who access assisted reproduction abroad cannot register the baby as the child of two mothers, according to a recent complaint by a family that moved to Belgium to conceive. In Hungary, where female partners cannot access artificial insemination or in vitro fertilisation, similar problems are common. “When the registration is taking place after the birth then the mothers are asked about whether there was a father. And if there’s obviously no father, then they have to tell something about the origin of the kid,” explains Sandor. Some people try to present documentation to prove that the baby was the result of ART, while others mention one-night stands and say they do not know the parent. “People [are] concerned about having to lie in front of a public notary. It’s something awful,” she says.

The situation in reproductive tourism host countries could change in the future. Irene Cuevas, coordinator of the Registry of the Spanish Fertility Society, points out that many women have traveled to Spain, especially to communities such as Catalonia and the Basque Country, for ART “because it was illegal” in their places of origin. However, the recent legislative change in France, which allows all women to access ART, regardless of their marital status or sexual orientation, will encourage such women to remain in their country. “The semen donation cycles will decrease above all,” says Cuevas. This could also happen in Belgium, another common destination for patients from France. For the French activist Magali Champetier, who traveled to Spain with her partner to have a baby, according to the magazine Komitid, “this will be less stressful, and in addition, it will be free, unlike abroad.”

Methodology

Olalla Tuñas and Miguel Ángel Gavilanes collaborated in this investigation. The journalist Adrian Burtin, from VoxEurop, conducted the interview with the French patient, whose contact was facilitated by the press office of the Dexeus Mujer fertility clinic. The journalist László Arató interviewed the Hungarian patient. The names of the two women have been changed at the express request of both. Information for Italy was provided by Giorgio Comai, from OBC Transeuropa.

We reviewed the scientific literature in databases such as PubMed and Google Scholar using search terms such as “reproductive tourism”, “fertility tourism” or “cross-border reproductive care”. We contacted the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) which, despite publishing data on tourism for personal reasons, does not disclose information on health-related travel.

We contacted the press offices of the ministries of health or social affairs of all the countries of the European Union to request relevant reports or records. There is no specific data or we did not receive a response from Germany, Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, Latvia, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Sweden. In the case of the United Kingdom, we reached the press office of the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). We did not rely on the figures published by the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) in its annual publications, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017, because ESHRE indicates that the information is “incomplete” and “not reliable enough to draw conclusions”.

We did not receive responses from the Public Gamete Bank of Portugal, the Repromeda Clinic in Czechia, the European Sperm Bank in Denmark, or the Homophobie organization in France. The IVI-Valencian Infertility Institute in Spain declined to answer all of our questions and the Unica Clinic in Czechia answered only some of our questions.

Déjanos decirte algo…

En esta información, y en todo lo que puedes leer en Civio.es, ponemos todo el conocimiento acumulado de años investigando lo público, lo que nos afecta a todos y todas. Desde la sociedad civil, 100% independientes y sin ánimo de lucro. Sin escatimar en tiempo ni esfuerzo. Solo porque alguien tiene que hacerlo.

Si podemos informar así, y que cualquiera pueda acceder sin coste, sin barreras y sin anunciantes es porque detrás de Civio hay personas comprometidas con el periodismo útil, vigilante y al servicio de la sociedad en que creemos, y que nos gustaría seguir haciendo. Pero, para eso, necesitamos más personas comprometidas que nos lean. Necesitamos socios y socias. Únete hoy a un proyecto del que sentir orgullo.

Podrás deducirte hasta un 80% de tu aportación y cancelar cuando quieras.

¿Aún no es el momento? Apúntate a nuestro boletín gratuito.